A Century of Brothels in Wallace, Idaho: An Overview

The podcast episode I’ve linked to above discusses some of the madams and brothels in Wallace, Idaho through the years, beginning in the early mining camp days and wrapping up with the early 1990s. Below is a transcript with pictures.

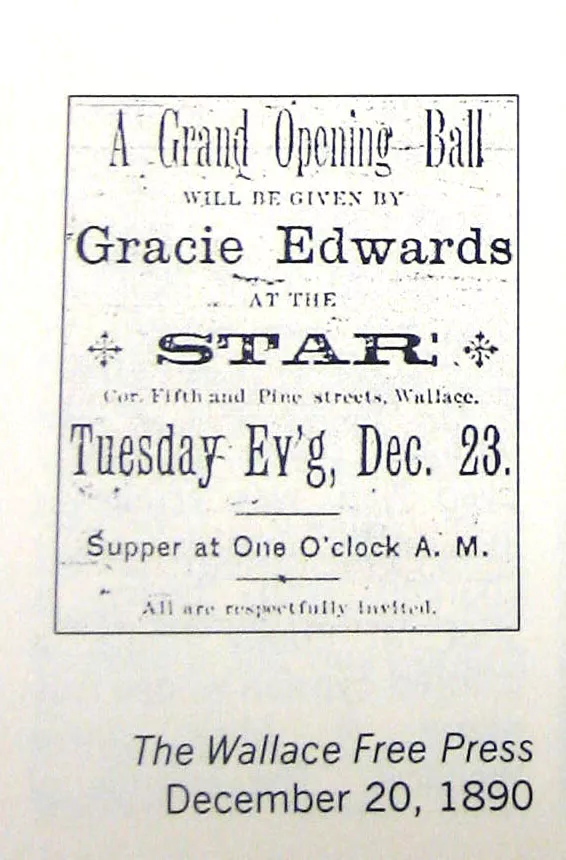

Some of the earliest evidence for the houses appears in 1890, in the form of sensational newspaper stories and even advertisements. In December of this year, an ad appears announcing a Christmas ball to celebrate the 1890 grand opening of Gracie Edwards’s The Star, a high-class brothel located at the corner of 5th and Pine.

The Star employed at least six women from 1890-1904.[1] Gracie’s parlor house featured crystal goblets, satin spreads, and pillow shams on the beds, following the example of larger city bordellos. Two of her girls gained fame one night when Lulu Dumont stabbed Frankie Dunbar with her stiletto seven times while fighting over money.[2] She survived.

Madam Effie Rogan ran a house called The Reliance on Pine between 5th and 6th streets during the 1890s. In about 1904, she moved from Pine Street to the alley behind what is today the Oasis Bordello Museum. Effie’s housemates reported their occupations as dressmaker and hairdresser to the 1910 census taker, but they were probably both working girls because the following year, Effie was in court for keeping a house of prostitution.[3] By 1912, she had been convicted of sex trafficking, which was referred to at the time as ‘white slavery.’[4]

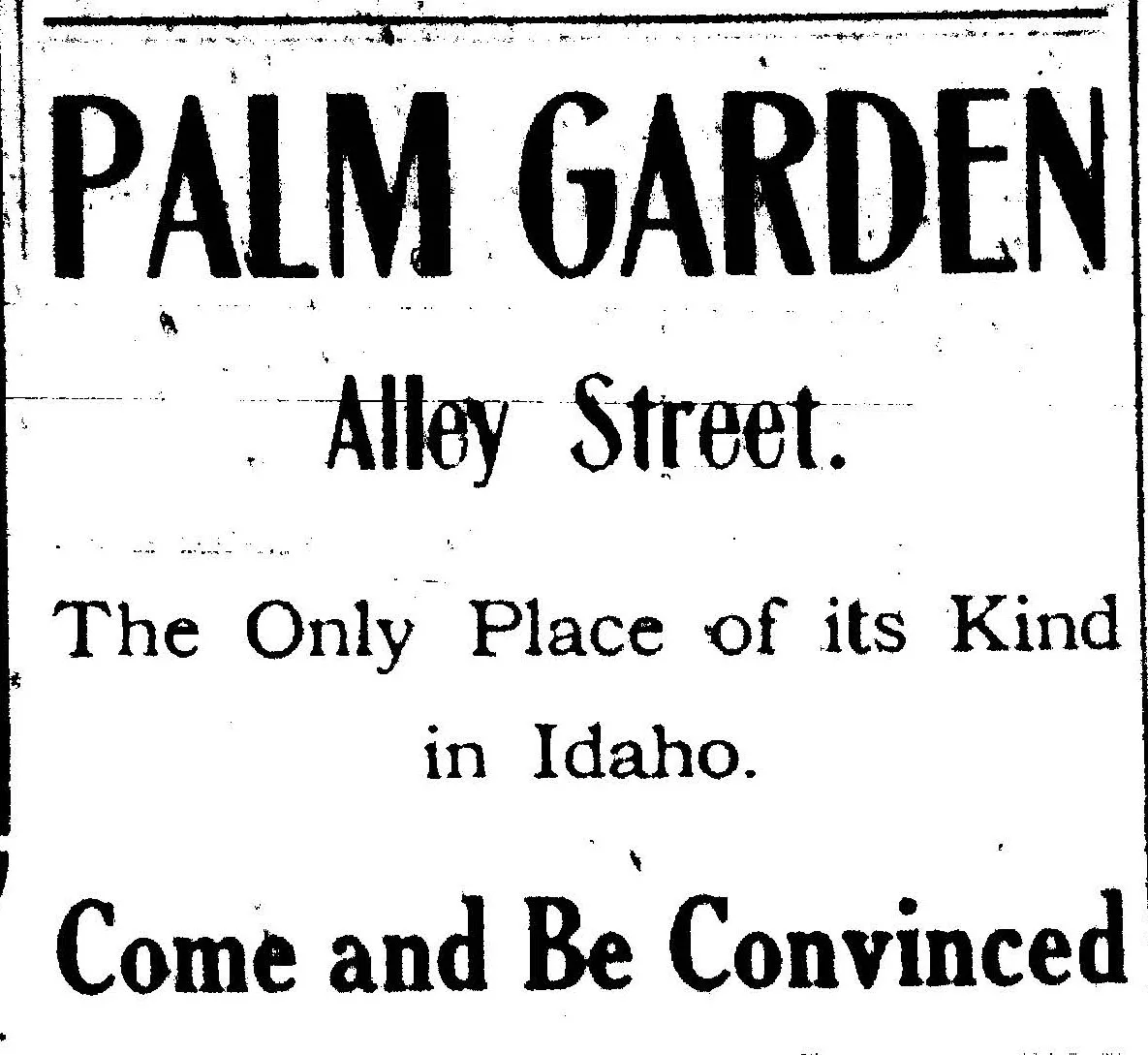

In 1908, the Daily Times features an ad[5] for an establishment in the red light district called the Palm Garden, managed by a woman named Jennie Girard from 1906-1911. The ad is rather vague about what happened there, saying only that the house is ‘The Only Place of its Kind in Idaho,’ and urges the reader to ‘Come and Be Convinced.’ This theme was consistent with Jennie’s style: she also ran a variety show out of a place called the Surprise Theater.

In 1910, four women worked for madam Connie Foss, whose house was also on ‘˜the Alley’ of ‘Block 23.’

![1908ConnieFossMadamAveA[8-P760]](https://findheatherlee.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/1908conniefossmadamavea8-p760.webp?w=625)

After President Teddy Roosevelt’s visit in 1903, the city began relocating the working girls to the triangle piece of land north of Cedar Street, between 6th and the river. This area would eventually become the ‘official’ restricted district.[6] By 1904, Mayor Rossi had mandated that ‘all lewd women’ would be confined ‘absolutely’ to Avenue A, the alley located here.[7] Rossi began to enforce this policy of separation and containment strictly in 1905, when he declared to the city council that prostitution was ‘a necessary evil,’ but that it must be limited ‘to its present quarters with a strong hand.’[8]

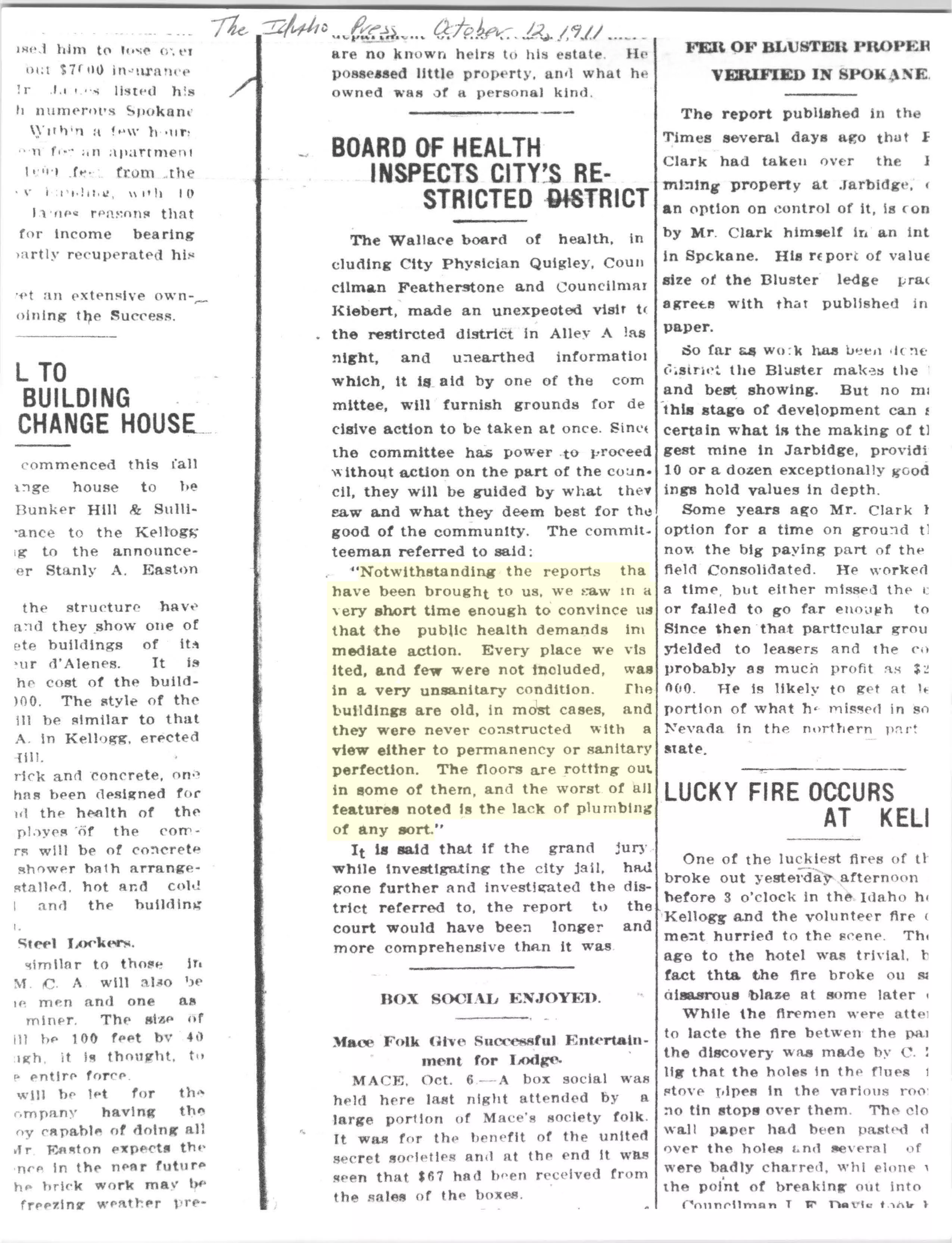

By 1911, much of the country had worked itself into a moral panic over prostitution, and many restricted districts closed completely. The Mann Act was signed into law one year earlier, and it prohibited transporting women across state lines for ‘immoral purposes.’ It was meant to target procurers and aid in the prosecution of those engaged in human trafficking and sex slavery. In the rough mining town of Wallace, full of single men, the thinking went that as long as vice was limited to Alley A, it was okay for some women to sell sex in order to, as Rossi put it, keep ‘virtue in the highest esteem’[9]‘that is, prevent other women from getting raped. So the concerns shifted to public health and social hygiene instead, as they soon would across the rest of the nation as well. In 1913 the red light district financed local improvements and was the first part of town to benefit from paved streets and other upgrades.[10] The city council voted in 1917 to grant the health officer oversight of the conditions there, setting the stage for medical regulation in the future.[11]

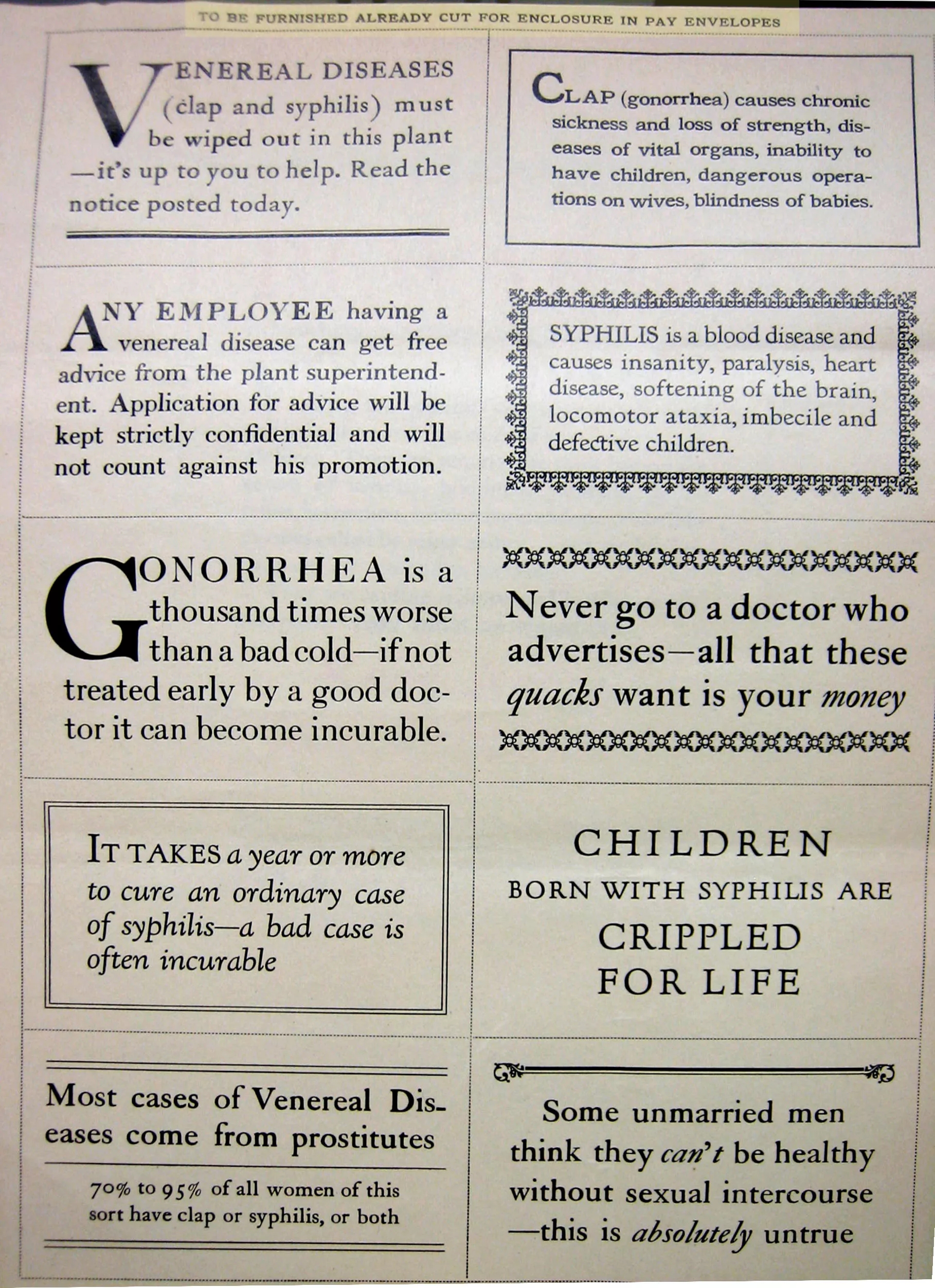

By 1917, the United States government had declared a war at home as well as abroad, launching a comprehensive campaign to eliminate the remaining red light districts across the country. This attempt was successful in many cities, but in towns such as Wallace, prostitution was such a part of the culture that it would not be eradicated so easily. The War Department teamed up with Brown manufacturing company to distribute ‘educational’ propaganda to sites of industry such as logging mills and mines. Fliers and pay stub enclosures, sent to the Potlatch Forests Company for distribution,[12] were meant to curb the demand for sex work through fear mongering.

The government also included suggestions for rhetoric appealing to patriotism and loyalty to country when giving safety lectures to workers. One flier warns, ‘Keep Away from Prostitutes Priced and Private. Most cases of clap and syphilis come from sexual intercourse with prostitutes (whores). 70% of all ‘˜loose women’ have both.’ This material seems a bit extreme, proclaiming that clap and syphilis ‘are among the most important causes of insanity, blindness, paralysis, impotence, barrenness, miscarriages, and many terrible diseases called by other names.’ While some of this propaganda is factually inaccurate, syphilis was a serious problem.

Josie Morin was a well-known madam at the U&I Rooms. For a Red Cross fundraiser during WWI, she gave a little girl named Mary Gordon White $25.00, which would be the equivalent of about $450-$500.00 in 2014 currency. Gordon White, who grew up in the house on 301 Cedar Street, wrote about her experience years later: ‘I rang the bell and a very nice lady asked me to come in. Her living room had pink shaded lights and a lot of shiny satin pillows, and she seemed very friendly and very pretty. [‘¦ When] I told about my lucky afternoon at dinner that night, my father said he knew her. She was a very generous lady. She gave money and other helpful things when needed’ and was ‘a very well-known madam who had a booming business in Wallace and the Coeur d’Alenes.’[13]

Babe Kelly was one of forty-four indicted by a grand jury for conspiracy to violate the Prohibition law in the event that came to be known as the North Idaho Whiskey Rebellion. In November of 1929, two weeks after the stock market crashed, the paper reported the wave of arrests by federal agents: ‘Some of the defendants were visibly affected as they were brought into Commissioner Walker’s office, but the majority laughed and chatted.[…] Most jovial of all was fur-coated Babe Kelly, who draped herself in a chair, lit a cigarette, and began ‘˜kidding’ the officers and telling jokes.’[14] These indictments were a pretty big deal at the time, and represent the second of three major federal raids in Wallace’s history, with the first being the intervention during the labor wars of the 1890s, and the third being the gambling raid in 1991. Local historian Dick Magnuson has pointed out that, when compared to other Volstead Act conspiracies, the unusual thing about the North Idaho Whiskey rebellion was that money paid to public officials went back to the local area, rather than into private pockets.

Anna Brass, aka Mrs. Julius Brass, was a madam on Avenue A during the 1920s. In August of 1931, The Health and Sanitation Committee, along with the fire chief and chief of police recommended to the city council that her brick building needed to be torn down because it was ‘so dilapidated and/or is in such condition so as to menace the public health and/or safety of persons and/or property on account of increased fire hazard and/or otherwise.’[15] If she didn’t remove it within ten days, the city threatened to demolish it for her and tax her for the cost.[16] She would, however, continue to run a brothel in the restricted district until at least 1937.[17]

After prohibition ended, women began to return to greater leadership roles within the community. For example, women such as Bess Ricard owned and operated their own joints again. Ricard’s was called the Pepper Box during the 1940s[18]. It may have simply been a bar, but was most likely a brothel that served beer and liquor and featured slot machines.

Gambling had been technically banned beginning around the turn of the century up until 1947, at which point in time the city council legalized ‘coin-operated amusement devices,’ and during this first licensing period alone, brought in about $22,000 dollars, which translates to nearly a quarter of a million today.[19] In 1938, the amount would increase to $38,000, or about $376,000 in today’s money. Then in 1949 the town expanded the ordinance to include ‘punchboards’ and other ‘chance prize games.’[20] A woman by the name of Ruth Poska also applied for such licenses under the name of an establishment called The Club, which was located where the Bordello Museum is today. She was likely the madam upstairs, which might have been called the Club Rooms at that time.[21]

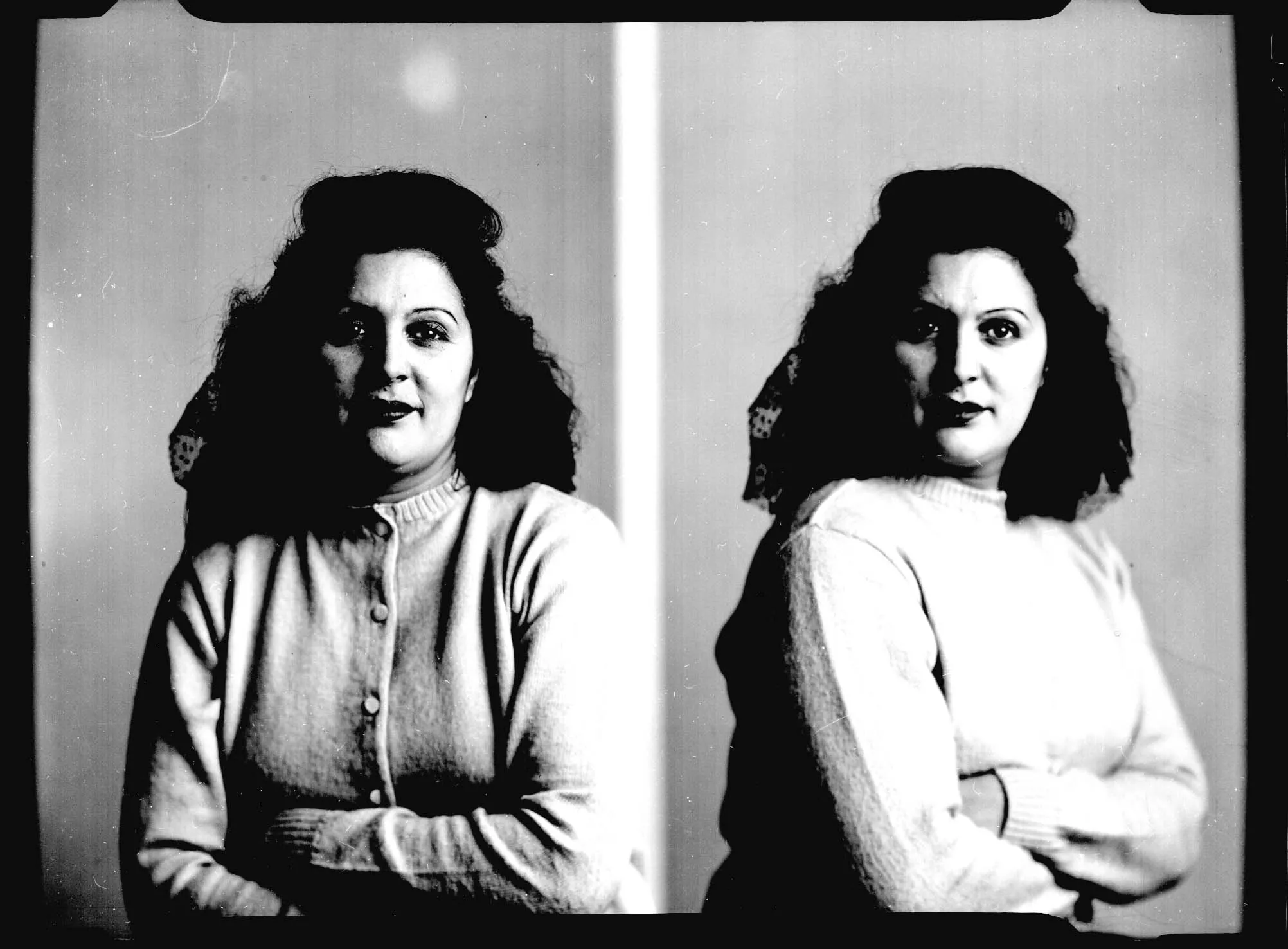

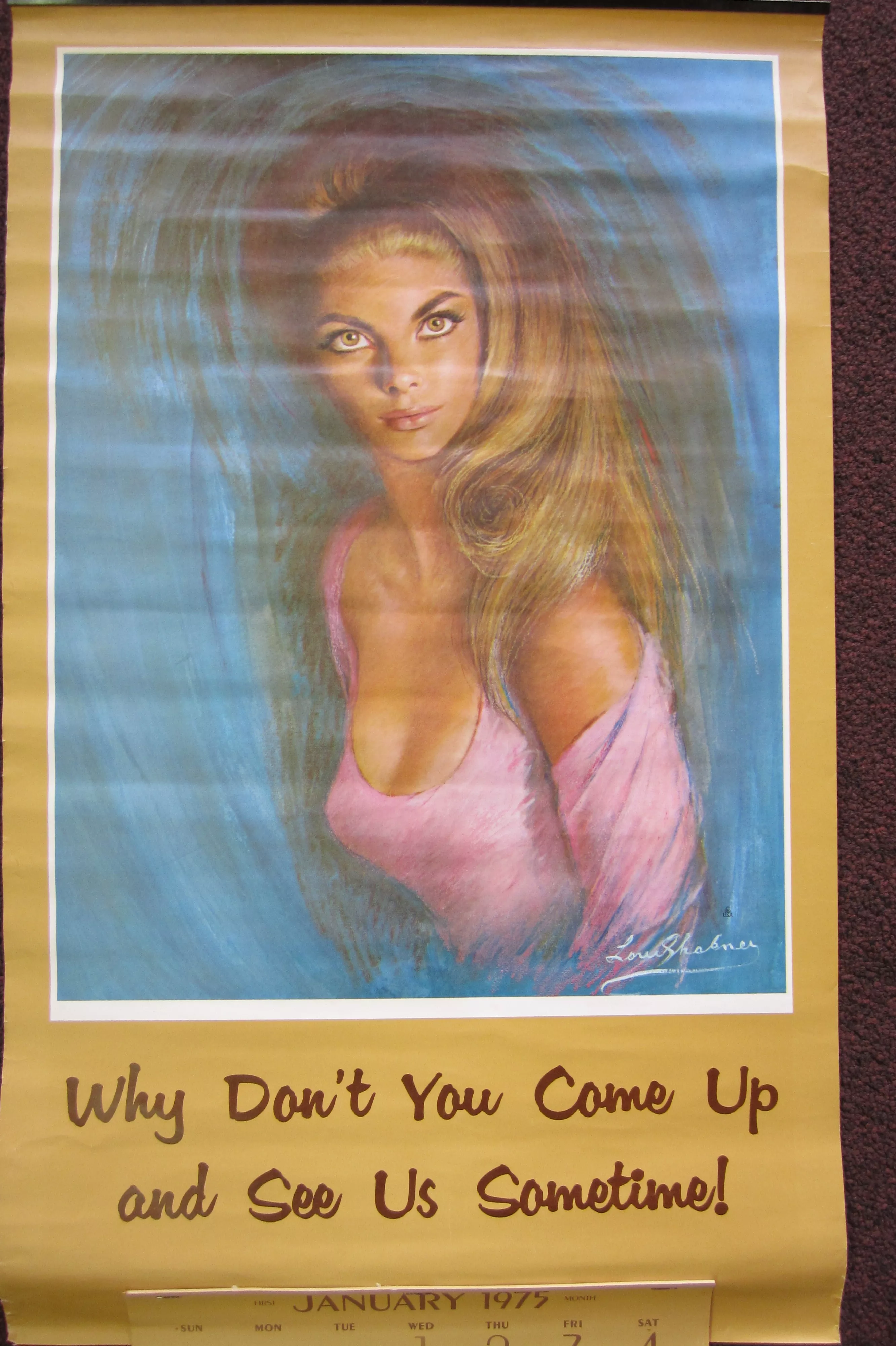

Dolores Arnold, was the ‘star’ madam of the post-World War II era. She first came to Wallace from Bremerton, Washington in 1943,[22] and by 1947 was in charge of the Lux Rooms. People say she could have been a movie star, ran her business in a ‘classy’ way, and was both respected and beloved by people around town.

Like Gracie Edwards had done fifty years prior, Dolores hosted Christmas parties for local businessmen and community leaders, and like Josie Morin twenty-five years prior, she gave generously to charitable causes, even turning some causes into a double-benefit: she bought so many raffle tickets that she would win, and then she would give away the prizes to families in need.[23] In 1972, she donated food baskets to the families of the 92 miners killed in the Sunshine disaster.[24]

Luoma Delmonte was also widely seen as a community leader. She was close friends with Dolores and competed with her in the realm of charitable giving.[25]

She came to Wallace in 1945 and had made over the Western Rooms into The Jade by 1953. Known around town simply as ‘Loma,’ she had a reputation for being funny and for unleashing a torrent of dirty words if you pissed her off.[26] Loma was a devout Catholic, and many of the profits from her house went to the St. Alphonsus church.[27]

Dolores and Loma set the standard for the way the houses would be run in Wallace. They ensured that the women they employed would not solicit on the streets nor drink in the bars around town, although they were allowed to visit the drug store, bank, buy paperbacks and magazines, and wire money to their families using Western Union. Around town, the girls were never to speak to a man first, for fear the man might become embarrassed at being recognized in front of others, or perhaps also because people worried that could easily cross the line into solicitation. These women both donated liberally to the city coffers and special community events, such as prizes for the fishing derby, when the town drained the pool, refilled it with creek water, and planted fish.

During this time prostitution was widely embraced and regulated by the town. Penicillin’s availability and effectiveness led to changing attitudes about sexuality nationally, and lessened the consequences of promiscuous or commoditized sex. Every woman who came into town had her picture taken by Nellie Stockbridge and also checked in and out with the police, who ran her rap sheet through the FBI records to see if there were items of concern and to double-check that she was over the age of 21.

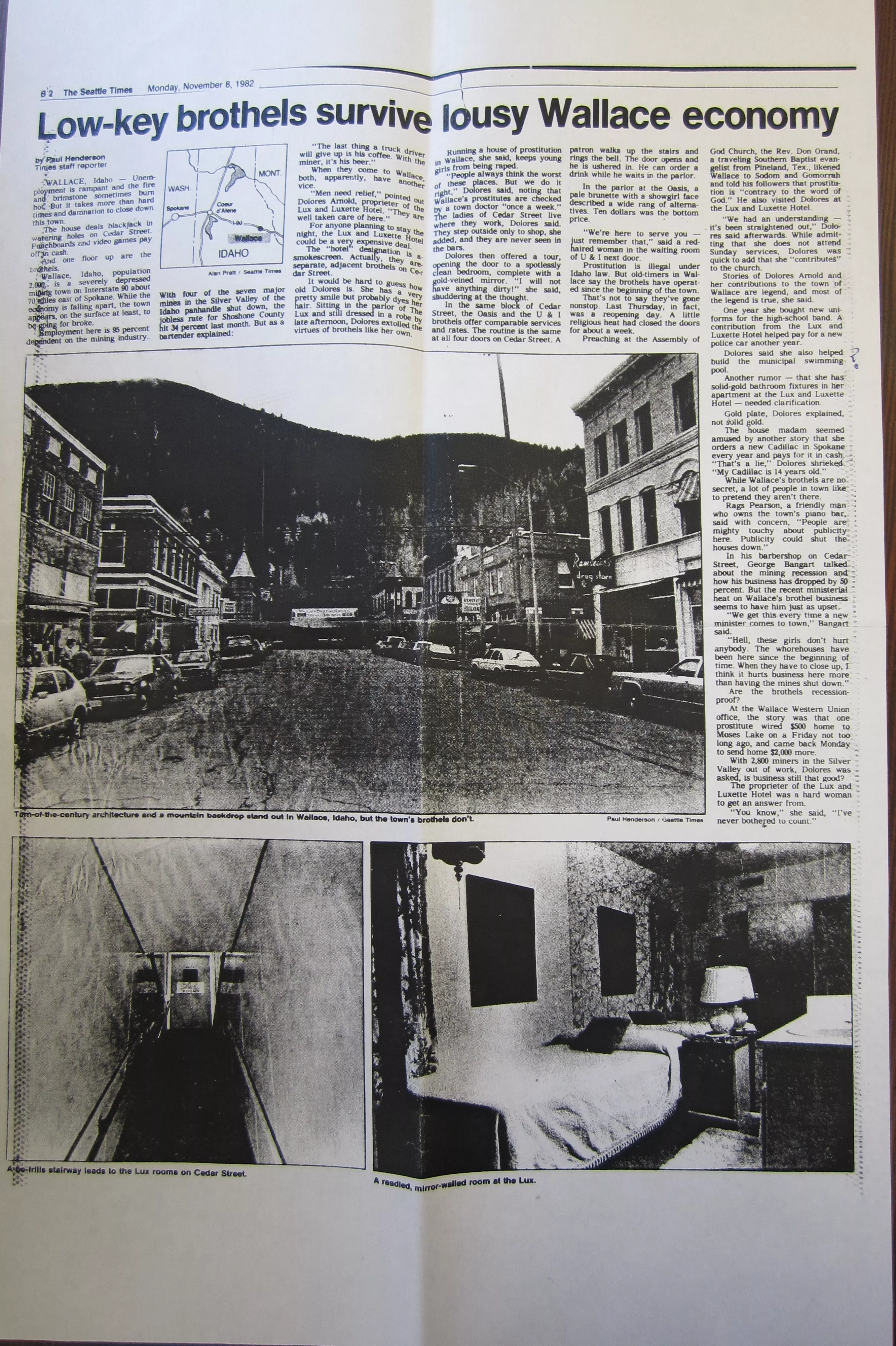

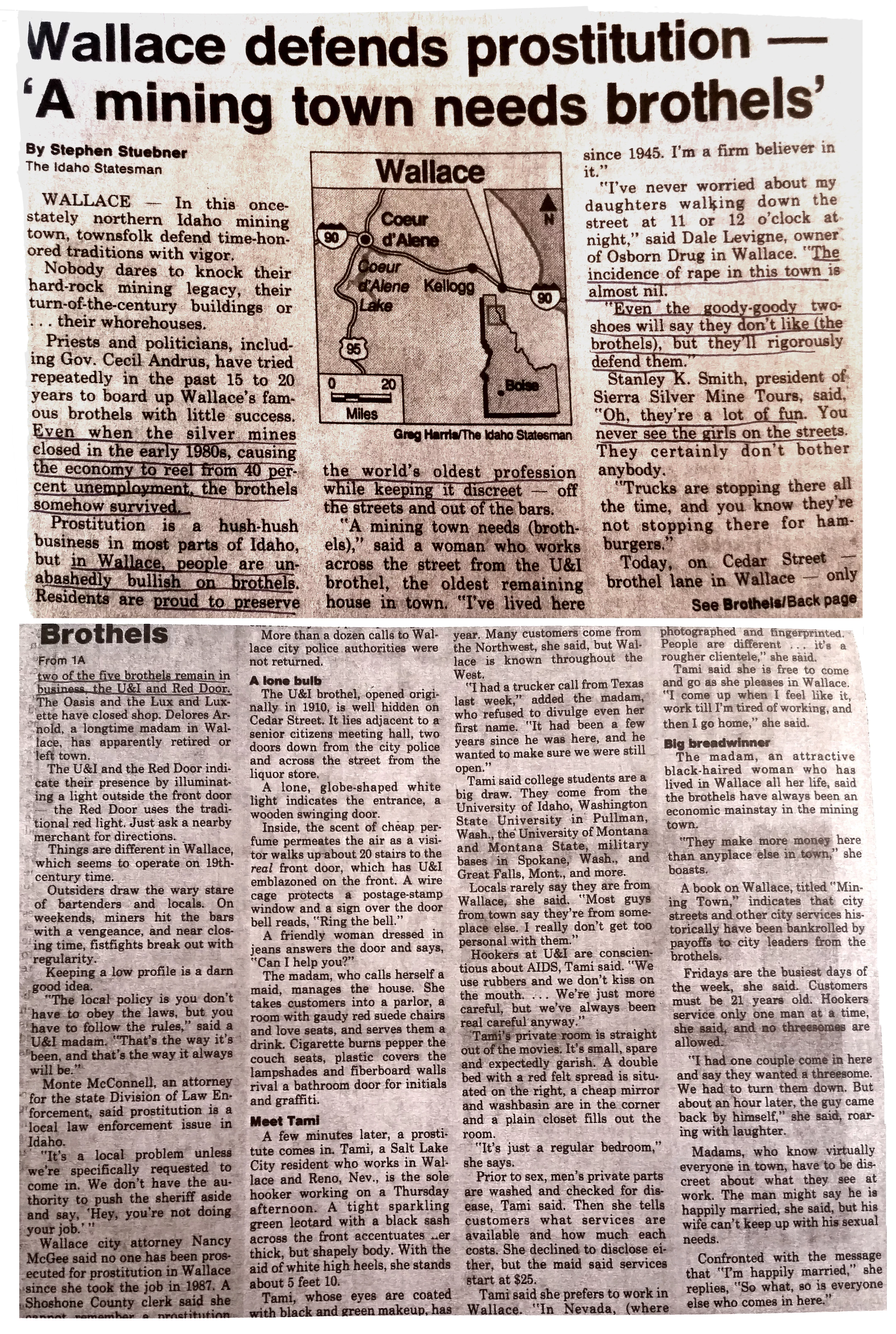

People who grew up in Wallace didn’t know anything other than sex work as a fact of everyday life. The community embraced its wild ‘live and let live’ mining camp attitude and the underground economy that went along with it. A New York Times article appearing during the 1973 shutdown confuses some things, but offers an example of the high degree of acceptance the community had toward the madams and houses, and illustrates how wide Wallace’s reputation had spread, noting that a bartender at Albi’s had fielded 14 long-distance phone calls that day to ask if it was true.[28]

The truth was, state laws had been reformed in the early 1970s and the long-simmering differences in culture between northern and southern Idaho came to a head when Stanley Crow, a so-called ‘moral crusader’ from the southern part of the state accused Governor Andrus of taking bribes to allow Wallace’s houses to continue operations instead of enforcing the new laws.[29] Afterward, the story goes, local businessmen Harry Magnuson and Hank Day got on the phone to Governor Andrus and said, ‘You run your end of the state and we’ll run ours.’[30] So the houses didn’t shut down for long, but the rooms on the second floors did operate more quietly for a while.

Police regulation appears to have ended in 1973, although the madams still enjoyed protection and continued donating money into a community fund managed by the chamber of commerce. Later claims that this amounted to bribery and corruption were not substantiated during two subsequent trials’it would be a misunderstanding of the community attitude and the legal evidence to interpret the arrangement the madams had with the town as anything other than mutually beneficial, reciprocal, and according to a 1977 study, was embraced by 75-80 percent of Wallace citizens.[31]

According to police records there was a house called the Sahara that employed four girls during the year of 1973, but nobody really seems to remember this house, and it’s possible that the Arment operated under this name for a brief time of back-stairs-entry-only during the temporary closure of 1973. That’s just an educated guess. Dolores apparently operated the Lux as a ‘massage parlor’ for a short period of time during this year, until concerns subsided and operations resumed as before, in an open secret, regionally accepted manner.

There were five established houses, all located on the second floors of downtown buildings. The Lux was at 212 ½ 6th St. with access from Kelly’s Alley, The Arment was above 601 Cedar St. until 1977, when it turned into the relocated Lux.

The Oasis was above 605 Cedar St, where the museum is today. Ginger, madam from 1963 until its closure, moved to Wallace from Hollywood, California.

Like Luoma, Ginger wasn’t very public around town, but she also donated to local causes such as the annual mining competition.[32] She drank black velvet and wore three hundred dollar pajamas, leaving her house only to make trips to the bank and to sign legal papers from time to time.[33] Her house, at 605 ½ Cedar, featured an incredible number of mirrors, following in the tradition of brothels like the Everleigh Club in Chicago and Babe Connors’s Palace in St. Louis.[34]

The Oasis is now a museum and novelty shop, preserved in much the way Ginger left it when she and the girls left town.

611 ½ Cedar St. was home to the Western until 1953, the Jade until 1967, and then the Luxette until the late 1980s. The U&I Rooms, referred to by the University of Idaho college students in Moscow as the school’s ‘northern branch,’ was located above 613 Cedar St. Lee Martin came to Wallace in the 1960s and ran the U&I Rooms at 613 ½ Cedar until its closure.

Once you were friends with Lee, you were friends for life[35]‘she was known for being loyal to her people, and once sent $500.00 to some local guys who’d run into trouble and gotten themselves stranded in Colorado.[36] Her approach to keeping the girls happy was to ensure they had a social life, so it was common during the 1970s and 80s for locals to go up to the U&I just to hang out and drink.[37] Some of them became so close that they called themselves ‘the family.’[38] Although you didn’t see the girls out at the bars around town, they did socialize more during the later years, developing friendships with local women as well.[39] Tanya arrived on the scene during the early 1970s. People talk about what a rookie she was when she first arrived but she was smart, liked her job, and had a head for business, so she advanced to a leadership role quickly,[40] assuming most of the management duties at the U&I by 1985.

The U&I, in the written record as early as 1905, would hang on until 1991, outlasting the others. The Oasis shut down in January of 1988, the Lux and Luxette closed around the same time, due to Dolores’s Alzheimer’s disease increasing in severity, and finally in September of 1990 the U&I was mostly closed. It remained open in a quieter way until early June of 1991, when, according to at least one account, an FBI agent confessed to Tanya ‘in a moment of weakness,’ warning her that a large raid targeting the illegal gambling would soon take place, and they should take the opportunity to leave town for good.[41]

Word is everything had mostly died down anyway, that the local economy could no longer support the workforce it had previously (unemployment soared to between 20-40%) and AIDS had really put a damper on the demand for the girls’ work. The century of brothels in Wallace was over, and the town transitioned into a tourism community, moving from selling sex to selling the past.

By Heather Branstetter, with generous support provided by The Wallace District Mining Museum and Virginia Military Institute.

If you would like to learn about the locations of the brothels through the years, along with maps, you can find that information HERE.

Personal Interviews and Research Assistance

Thank you so much for your contributions to and participation in this project:

Mitch Alexander

John Amonson

Katie & Joe Bauer

“Betty”

“Bobby C”

Ken & Joann Branstetter

Mike & Nancy Branstetter

Dick Caron

Terry Douglas

Bob Dunsmore

Sam Eismann

Mike Feiler

Merrill Field

Nick Fluge

Penny Caron Garr

Fred & Debbie Gibler

Kristi Gnaedinger

John & Sue Hansen

Tom Harman

Rod Higgins

Patti Houchin

Archie Hulsizer

Butch Jacobson

Richard Magnuson

Michelle Mayfield

Jim & Peggy McReynolds

Penny Michael

Lynn Mogensen

Bill & Karen Mooney

Gary Morrison

Moe Pellissier

John Posnick

Justin Rice

Ron Roizen

Chase Sanborn

Patty Schaeffer

Tammy Schonhanes

Julie Austin Stewart

Eva Truean

Dick Vester

I am also grateful to be surrounded by incredibly smart professional colleagues and mentors who have influenced and inspired my thinking on this project. Dan Anderson, Risa Applegarth, Gordon Ball, Kelly Bezio, Erin Branch, Julie Brown, Jameela Dallis, Jane Danielewicz, Sarah Hallenbeck, Jordynn Jack, Kristen Lacefield, Jim McReynolds, Chelsea Redeker, Lindsay Rose Russell, Rose Mary Sheldon, and Todd Taylor: thank you so much for your contributions, advice, and encouragement.

Bibliography and Notes

Abbott, Karen. Sin in the Second City: Madams, Ministers, Playboys, and the Battle for America’s Soul. New York: Random House, 2007. Kindle Edition.

“Board of Health Inspects City’s Restricted District.” Idaho Press, 12 October, 1911.

“Five Brothels Shut in an Idaho Town.” Special to the New York Times, 5 November 1973, pg 17, via ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Powell, Cynthia S. Beyond Molly B’Damn: Prostitution in the Coeur d’Alenes, 1880-1911. MA Thesis, Central Washington University, 1994.

Shoshone County Courthouse District Court Records.

Smith, Donna Krulitz. “It Will All Come Out in the Courtroom’: Prohibition in Shoshone County, Idaho. MA Thesis, University of Idaho, 2004.

Wallace City Council Minute Books.

White, Mary Gordon. “A Child’s Eye View” Personal Narrative. Wallace District Mining Museum Archival Collection.

[1] Powell 51.

[2] ‘The Stiletto. It is Used by One of the Fallen Sisterhood with Serious Result.’ Wallace Press 10 October 1891, qtd. in Powell 74 and Moynahan.

[3] Shoshone County Court House, District Court Office, Index to Register of Criminal Actions; Proceedings Book B, No 497, qtd. in Powell 48.

[4] Powell 48 and 59.

[5] Tom Harman primary sources files in 2014 Wallace District Mining Museum (WDMM) Brothel Project digital repository.

[6] Spokesman-Review articles in Dick Caron files, 2014 WDMM Brothel Project digital repository. City of Wallace, City Council Record Book, 28 October 1901 to 10 September 1906, Minutes of Council Chamber, 24 April 1905, qtd. in Powell 104-105.

[7] Powell 104.

[8] Powell 104.

[9] Powell 104.

[10] City of Wallace Council Minute Books, 1913-1916, pgs 30-36, 22 September 1913.

[11] City of Wallace Council Minute Books, 1916-1923, pg 167, 10 September 1917.

[12] Potlatch Forests Papers, MG 96 Box 4, “Military.”

[13] Mary Gordon White, ‘A Child’s Eye View,’ personal narrative, WDMM archival collection.

[14] Wallace Press-Times 11/14/29, pg. 1

[15] Wallace City Council Minute Book 1931-1939, 24 August 1931, p. 423

[16] Ibid., pg 424. The legal description indicates this building was just behind and moving toward the East of where the Oasis is today.

[17] Wallace City Council Minute Books, 1931-1939, 14 December 1936, pgs 658-659.

[18] Wallace City Council Minute Books, 1939-1947, 8 January 1945, pg 958.

[19] Wallace City Council Minute Books, 1939-1947, Ordinance 292, 24 March 1947, pg 1024-1028. The State of Idaho and Shoshone County each received a quarter of this money, while the city kept half (pg 1026).

[20] Wallace City Council Minute Books, 1947-1960, Ordinance 300, January 1949, pg. 1085.

[21] Richard Magnuson told me (2014 interview) he thought the Oasis was called the Club Rooms. Police records document that it was known as the Oasis by 1952.

[22] Picture records, Barnard-Stockbridge Collection. Town of origin information, Lynn Mogensen and Eva Truean (2014).

[23] Personal Interview with Gary Morrison (2010).

[24] “Five Brothels Shut in an Idaho Town.” Special to the New York Times, 5 November 1973, pg 17, via ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

[25] Personal Interview with Richard Magnuson (2014).

[26] Reverend Dr. Jim Ranyon personal narrative (2008) in Dick Caron files, WDMM Brothel Project digital repository.

[27] Phone Interview with Penny Garr (2014).

[28] “Five Brothels Shut in an Idaho Town.” Special to the New York Times, 5 November 1973, pg 17, via ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

[29] Personal Interview with Richard Magnuson (2010 and 2014).

[30] Personal Interview with Dick Vester (2010).

[31] Buddy Miles Survey on Attitudes Toward Prostitution, MA Thesis, Washington State University, 1977.

[32] Personal interview with Penny Michael. The Oasis Rooms is listed, along with the Lux and Luxette, among the contributors to the first contest in 1984 (can be found in primary sources in the digital 2014 WDMM Brothel Collection).

[33] Personal Interview with ‘Art’ (2010) and Richard Magnuson (2014).

[34] Abbott, Karen. Sin in the Second City: Madams, Ministers, Playboys, and the Battle for America’s Soul. New York: Random House, 2007. Kindle Edition. Chapter One, Kindle Locations 340-345.

[35] Personal Interview with Patti Houchin (2014)

[36] Story independently told during personal interviews with Bill Mooney (firsthand knowledge of the story, 2014) and John Posnick (secondhand knowledge of the story, 2010).

[37] Personal Interviews with Chuck Roberts (2014) and Bill Mooney (2014).

[38] Personal Interview with Chuck Roberts (2014).

[39] Kristi Gnaedinger (2014), Patti Houchin, (2014).

[40] Personal Interview with Kristi Gnaedinger (2010, 2014), Chuck Roberts (2014), and Bill Mooney (2014).

[41] Personal Interview with Sue Hansen (2010 and 2014).

Please tell me what you think:

[contact-form][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Comment’ type=’textarea’ required=’1’/][/contact-form]

Leave a Reply