Were there ever any women of color who worked there [in the brothels]? You know, for guys who wanted someone a little more, you know, like, ‘exotic’ or ‘spicy?’

Kayla, the events coordinator for Auntie’s Bookstore in Spokane, asked me this question after my reading last week. She trailed off toward the end of her question, explaining that she was unsure how to ask about it and didn’t really know whether or not to ask about it at all. She worried it might make me uncomfortable, which is why she waited until after the event was over and I was just signing books for the store’s stock.

Kayla added:

As a black woman, I often find myself wondering about race at these kind of events, especially when it’s about history. Especially because this area is pretty white.

Before answering her question, I admitted that I felt like I didn’t address the topic adequately in the book. I wasn’t sure how to fit in some of what I had learned, in part because I was ashamed of it. (Especially the part that Possie discusses in the oral history I include later in this post.)

After the weekend’s racially-motivated violence in Charlottesville, however, it occurs to me that Kayla’s question was timely and others might be curious about it as well. So I thought I might talk about race and Wallace’s whorehouses in this post.

There were definitely women of color who worked in the houses all the way through the history of sex work in Wallace. In the book’s first chapter, I wrote about race in the early days of the mining camp. Here’s what appears on pages 37 and 38 (with brackets indicating sources that I footnoted in the book):

Newspapers reported several black women who were madams or sex workers as well. Even though race relations in the area were intolerant, African American women in Wallace lived in red-light districts, where they often operated laundry facilities and sometimes worked as sex workers as well, [Cynthia] Powell explained [in her thesis, “Beyond Molly B’Damn: Prostitution in the Coeur d’Alenes, 1880-1911”], adding that ‘there existed an indisputable demand for black prostitutes during the labor war of 1899, when a black regiment was brought in to quell labor tensions.’ According to [Richard] Magnuson, the government chose black soldiers in particular because they were seen as less likely to befriend or sympathize with the miners.

Like the white women, black sex workers appeared in the paper most often because of violence or crime. [According to Powell’s research,] Ella Tolson, ‘who lived over the Troy Laundry in Wallace’s Pine Street sector,’ was reported to have shot Howard B. Johnson, who was ‘described as ‘˜the most widely known colored man in Wallace.” Irene Thornton owned a laundry business and the land it occupied in Wardner before moving to Wallace, where she was arrested for ‘conducting a disorderly house.’ [footnoted reference: Idaho Press, March 18, 1905] On March 25, 1893, the Coeur d’Alene Miner reported that ”˜a colored woman who live[d] on the opposite side of the street,’ from the disreputable Montana Saloon, witnessed a brutal beating. Her vantage point, according to the newspaper’s description of her Wallace location, was an ‘˜Avenue A’ crib.’ In the Silver Valley, black men and women seem to have inhabited roles that were relegated to Chinese immigrants in other western mining communities.

Here’s the context for Magnuson’s comment about the black labor regiment:

The town used to have blacks, but after the labor wars there was a stigma against them working underground. The black soldiers hadn’t been trained for the Spanish-American War, so that was why they came to Wallace. Also, they had less likelihood of fraternizing with the families and getting close to the prisoners in the bullpen. For a while Hank Day had a black maid in his household, but she left after a few years because she didn’t really find anyone to be friends with.

(You can read more about black regiments and/or so-called “Buffalo Soldiers” elsewhere, but I’m sorry to say I’m not the person to ask for recommendations on that topic. I’ve heard good things about John Langellier’s book, Fighting for Uncle Sam: Buffalo Soldiers in the Frontier Army, but I’ve not read it.)

And here’s the context for the last sentence in the book excerpt I quoted above, about black men and women inhabiting roles relegated to Chinese immigrants in other mining communities:

Unlike most mining camps, there was not really a significant presence of Chinese men and women in the early days of the Coeur d’Alene district. Patricia Hart and Ivar Nelson’s book Mining Camp talks a bit about this, but there are other published sources that reiterate this point. The few Chinese miners who braved this area faced deadly racism. I remember seeing signs for the “Silver Terror” mining claim when I was younger, and they chilled me because of the story my dad told me about their origin. Apparently the mining claim was so named because white miners stole it and hung the Chinese miners who’d discovered it. And that is why Terror Gulch is named Terror Gulch, according to the story.

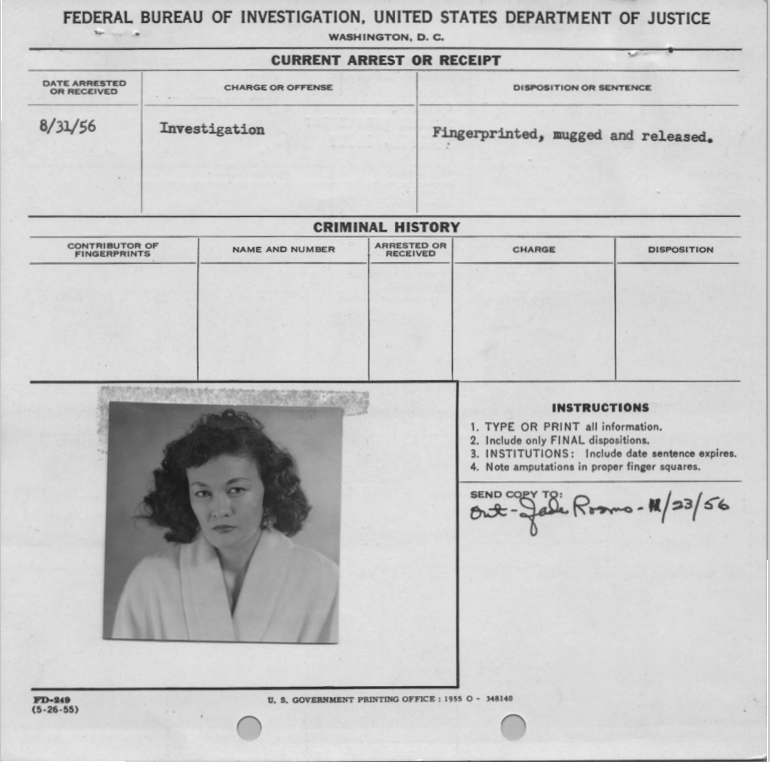

There is physical evidence that women of color worked in the houses throughout Wallace’s history, however. In the Shoshone County Sheriff’s Office records, which document the women who worked in the houses from 1952-1973, there are pictures of women who look African-American, Asian, and Latina or Hispanic, even though their records don’t list their race as such.

Other women in the Shoshone County Sheriff’s Office files were described as “red” (for American Indian) or “Mexican.” Sometimes a specific American Indian tribe is listed. And the earliest records have a category for “color” instead of “race.” It looks like police officers either struggled with accounting for race because they assumed instead of asking, or some women purposefully tried to pass as a different race. For example, when one woman originally labeled “white” was later found to be biracial, the officers annotated her file by hand, writing, “this woman is mulatto” next to her picture. Another file shows a woman’s race changed to “Chinese.” Sex workers were sometimes labeled “white” under the race category, but then in another section, the officers describe her as “olive-skinned.”

The Barnard-Stockbridge Collection at the University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives has pictures featuring women of color who worked in the houses during the 1940s-1960s.

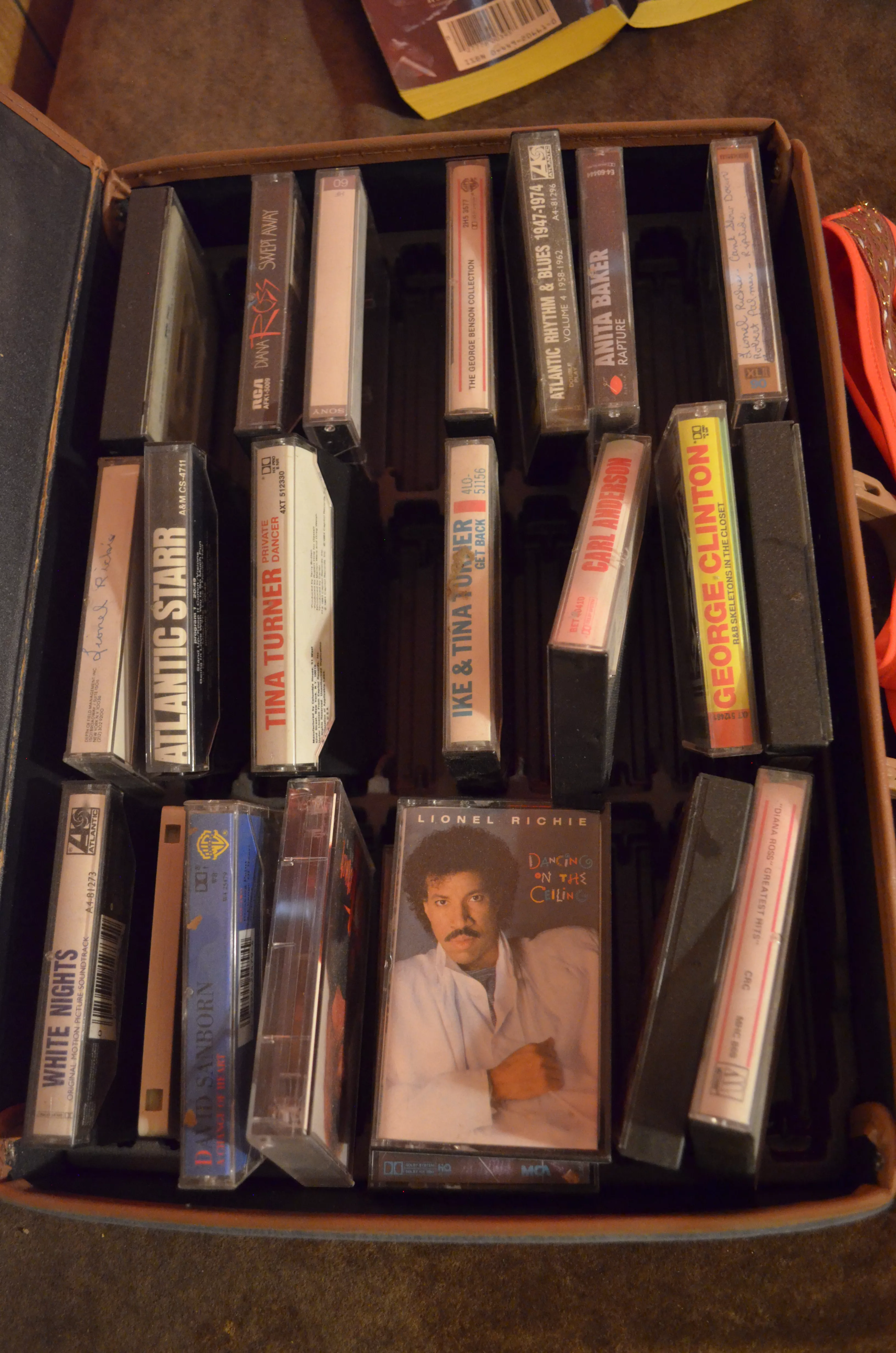

And the Oasis has one room with cassette tapes left behind by a sex worker in 1988, and these tapes feature mostly black recording artists and labels.

Oral histories also describe women of color in Wallace’s houses throughout history. Dick Caron has heard about a black woman who ran a house during the late 1930s and he thinks her name was possibly Rose or maybe people called her “Snowball.”

There is one oral history piece that I thought about putting in the book but I didn’t. I’ll just go ahead and put it out there now because Kayla and Charlottesville have me wondering if I should have included it in the book…

This is from a conversation at the Silver Corner, August 5, 2010:

Me: Were there any women allowed in the houses, aside from the women working there?

Possie: No. There’s a couple of times we’d try to get the women up. Yeah, you’d try and dress them up in a hat, or a ski mask, or something. Try and get them up there. And same thing with black guys, couldn’t get a black guy up there. They wouldn’t—

Bar patron interrupts: Is that true?

Possie: Definitely. We tried. We had a basketball tournament here in the early [nineteen] eighties. They would not let a black guy up there. The rumor was, because of Hank Day. He didn’t want anyone black.

Bar patron: Did Hank Day have an economic interest in those houses?

Possie: Oh huge. Hank Day was, you ever see [name omitted] house on the lake? That house was designed for whores. I mean the whole thing is like a motel, with separate rooms. He’d have the whole whorehouse down there.

Me: He’d have them there, or he’d hole up in the Lux Rooms, I heard.

Bar patron: What was his aversion? He was just a racist?

Possie: Well, I don’t know. I mean, yeah, probably. I don’t know if that’s, but I mean it was just, that was kind of the—yeah, he just wouldn’t allow it.

Second bar patron: Hank Day, like the Henry L. Day Medical Center Hank Day?

Possie: Yeah.

First bar patron: Like the Day Mines.

Possie: I’m gonna say, late [nineteen] seventies, early eighties.

Second bar patron: So when the black guys couldn’t get up there, was that before the civil rights movement, or afterward?

Possie: Afterward.

First bar patron: Well there weren’t that many black guys to begin with, Idaho’s not filled with African-Americans. Look around.

Possie: We had a basketball tournament here in the early eighties and it was I think [19]82, ’83, ’84, and it was big, it was a real big tournament, we had guys from Washington State playing, Gonzaga, Eastern Washington, Montana, Boise State, Idaho State, University of Idaho when Idaho had the good teams. Early eighties we were number seven in the country, we had them up here. And we got, we tried to get some of the guys into the whorehouses. And we even went before, trying to meet with them [the madams].

We didn’t want those guys coming here and thinking we were a bunch of racists. And see, we’d try to head it off before it happened. We wanted them to be able to come up to the whorehouses and you know, we didn’t want like the white guys only to be able to go up there, but they wouldn’t budge.

Second bar patron: You asked permission, and they were like, no?

Possie: We asked permission and didn’t get it. They would not budge.

But they were polite about it. They wouldn’t say, like, ‘No n*****, or no blacks,’ or anything.

They’d just, they always, when you’d want somebody, they’d say, ‘The girls are busy now, the girls are busy now. Come back later, the girls are busy.’ But they’d never—they’d look through the little peepholes, the glass thing, and they wouldn’t let them in.

First bar patron: Were they worried about trouble in there, probably?

Possie: Who knows.

Then, in my notes of this discussion, I stopped the transcription here to write:

Silence. Pos turns the music up.

Leave a Reply