“You pretended to have an orgasm? Is that a common practice among prostitutes?”

“It’s a common practice amongst anyone with a twat.[…]”

“But why, why would a woman lie about something like that?”

“Gawd almighty, this is… Okay, I’m gonna be honest with you but only cause I like you and you seem real dedicated about your project with your penguin suit and all, with the charts and the timer, but seriously, if you really want to learn about sex then you’re gonna have to get yourself a female partner.”

I was just re-reading provisional diagnosis: prostitution because I was thinking about how I didn’t get around to the main point I originally intended to discuss when I began that post. I wanted to say something more about the ethics of telling real people’s stories. Since then, I’ve checked out a couple relevant items of pop culture my friends told me about and revisited two books I read over the summer:

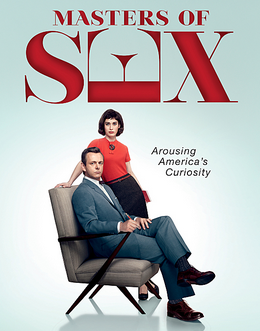

1. the Showtime series, Masters of Sex (based on a book about revolutionary human sexuality researchers Masters and Johnson),

2. the new podcast series, Serial, which re-investigates the murder of a teenage girl in 1999,

3. Karen Abbott’s book, Sin in the Second City, a historical account of the Everleigh Club, the famous early 20th century-era Chicago brothel, and

4. Alexa Albert’s Brothel: Mustang Ranch and its Women.

I’ve only seen four episodes of Masters of Sex, and so far I’ve been drawn in by the subject matter, of course, but I’ve also been impressed by the show’s attention to the research itself. The exchange I quoted above, which occurs between Dr. Bill Masters and a woman he found in one of St. Louis’s brothels, illustrates just one important role sex workers played in his initial research. Although the TV version changes things a bit, according to Maier’s book, it was the suggestion of one college-educated woman “‘amplifying her income for an impending marriage’ by dabbling in the sex trade” that “changed everything” for Masters (82), opening his eyes to the importance of finding a female research partner. [Sidenote: I thought Lizzy Caplan was awesome in Mean Girls and True Blood, but she’s really a great match for this role, as Gini Johnson.] I love how the first few episodes highlight the simultaneous importance and difficulty of studying or talking about sex in a culture that is mostly square and/or opposed to women having sex outside the confines of marriage.

After listening to the first two episodes of Serial, I have been inspired by the production quality–Sarah Koenig’s storytelling is compelling and experiments with the podcast genre in cool ways–and I’ve also been drawn into the meta-level-story-about-the-story, which involves real life people. A recent article by Michelle Dean in The Guardian features the following commentary about the consequences of documenting the lives of living people:

“But in the post-listening haze, as I poked around myself and discovered the social media undergrowth amassing under it, I began to have questions about what I was participating in. Serial is, after all, not a work of fiction. It is about real people.”

Which brings me back to what I wanted to talk about a few weeks ago… I’m just beginning to share this research that tells the story of my hometown and its people, and I’ve done a lot of the groundwork necessary to share it in an ethical way, but as with so many things, the devil is in the details. For example, I obtained institutional review board approval for my study, which means that I’m going beyond the ethical obligations and documentation that creative nonfiction writers or documentary journalists are bound to uphold. I offer anonymity for those who want it and obtain written informed consent from those who are willing to have their names associated with their stories. But the town is so small that in the case of one particular john who has shared his story with me, if I say much of anything to describe him, many people around Wallace will know exactly who I’m talking about.

And it’s not just living people I’m concerned about protecting. In the case of another person who is no longer alive, people have told me rumors about the nature of his sexual desires that, if I shared them, would be recognizable to some around town. And enough people would know who I was talking about that sharing the information might cause some to think that I was not being “respectful” of his memory (as my dad put it). But the people who shared these memories of this person wouldn’t have agreed with that opinion.

A big part of what I want the eventual book to do is bring to life the real women who ran and worked in Wallace’s brothels throughout history, while also connecting to the social context for debates about regulation vs. anti-prostitution vs. sexual liberation perspectives of prostitution. Sort of a combination of items 3 & 4 I listed above. Abbott’s historical nonfiction book about the impact of the Everleigh sisters takes us into their Chicago parlor house and its women through archival and newspaper sources, while Albert’s sociological and biographical portrayal of the Mustang Ranch arose from in-person observations (which began as a study of condom use). Both books offer explorations of the sex work industry in nuanced and relevant ways.

I think we should be talking more about sex and sex work in these sorts of ways, connected to real history, real people, and real debates that actually impact our lives. We are living in a time that is unprecedented in terms of the availability and ubiquity of sexual imagery, videos, and toys, yet it’s still considered “inappropriate” to talk about in public middle-class settings. Instead of more information and better education, we’ve opted for censorship and underground exchanges. As a result, we aren’t adequately addressing the range of possibilities on the spectrum of the subject. For example, most people aren’t aware that even vocabulary indicates a moral position in the polarized “sex wars” debate: the word “prostitute” is seen as offensive to those who prefer the term “sex worker,” in order not to degrade the people engaging in the work; others think that to call it “sex work” is to normalize what they believe should be condemned as a violation of human rights (see The Idea of Prostitution, by Sheila Jeffreys for more on this)…

The aforementioned devil in the details comes down to people’s attitudes about sex, what constitutes sexual deviance, and how much of a person’s sexual preferences should be the topic of public conversation. These attitudes are influenced by socioeconomic class and religion, obviously, but the topic itself remains shrouded in hushed tones or controversy. So it’s pretty easy to make the argument that in American culture more broadly, sex is still considered to be an off-limits and “personal” subject. Or, as was the case for one man I met recently, there is the even more extreme opinion that Americans’ more recent liberated attitudes toward sex has led to the destruction of marriage and families.

Hmm. I need to wrap this up for now. But next time I’ll pick up where I left off, so I guess this is part one in what will probably become a three-part series of posts about morality and sex work.

Leave a Reply