What I do is perfectly legal when it’s free.

— Maggie McNeill

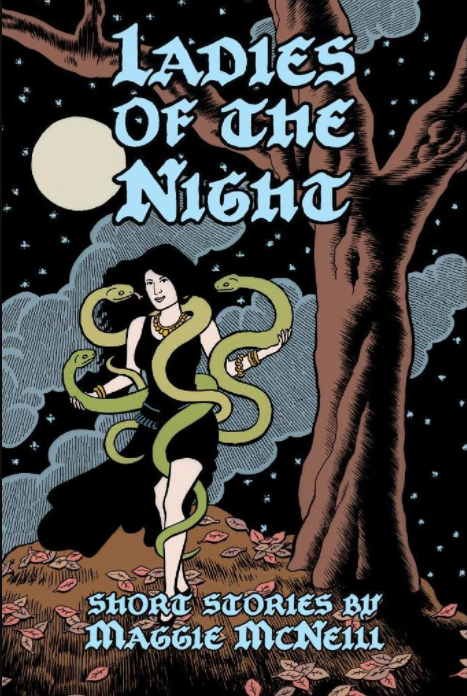

Today I am excited to finally share an interview with the lovely Maggie McNeill aka The Honest Courtesan. McNeill lives in the Seattle area, where she is a whore for hire and outspoken advocate of sex worker rights. She writes a popular blog, which you can find here, where you can also buy a copy of her book, Ladies of the Night.

In July 2015, McNeill took time out of her trip to visit a gentleman in Sandpoint to chat with me about the topic of sex work, morality, and politics. This topic has received a lot of attention in the time since we talked. McNeill and her Seattle colleague Mistress Matisse were featured in a widely-read and controversial New York Times Magazine article, “Should Prostitution Be A Crime?” for example.

Unfortunately, my talk with McNeill didn’t make it into my book, since my initial readers thought it didn’t really “fit” with the rest of the story about Wallace, although she does weigh in on the Silver Valley’s brothel-based model toward the end of the interview… McNeill calls herself “an overeducated whore who talks too much,” but I enjoyed our discussion very much and hope you will, too. I’ve excerpted the highlights below.

‘I am a whore. That’s what I am. It’s funny to see people struggle with that,’ Seattle sex worker and human rights advocate Maggie McNeill tells me as we begin. She is blunt with me about her profession of choice. ‘Rigidity on this subject needs to be broken,’ she explained.

As we talk, she touches my knee several times and instantly makes me comfortable and sexually desirable. She does most of the talking, but I somehow feel deeply understood and connected.

McNeill explains that she earned a master’s degree in library science but her real specialty is the GFE, or ‘girlfriend experience.’ She is lucky, she says, that there is a lucrative market for this talent. Many men want an approximation of what it would be like to have a girlfriend for the evening or weekend, and she helps them fulfill this fantasy.

Our business is pleasure. We like to say, “It’s a business doing pleasure with you.”

The amount of money McNeill makes per night ‘doesn’t make me any better than anyone else.’ To imagine otherwise is to buy into ‘whorarchy,’ which is ‘this notion’and the general culture promotes it, and some whores internalize it’that certain forms of selling sex are better, purer, cleaner, nicer’ than others.

The fact of the matter is: all of us, from trophy wives to streetwalkers, to dommes, to girls working in jack shacks, to porn performers, to phone sex operators, we’re all doing the same thing.’¦We are [all] making our money because men need to stick their dicks somewhere, and they are willing to pay money to do that.

Whorarchy is not only a logical fallacy but also a ‘dangerous’ illusion diving a community that should be unified to improve working conditions and fight stigma, McNeill adds, because sex workers ‘need to stick together, not fight amongst ourselves. The more inclusive movements are best.’

McNeill tells me that the widespread cultural perception that sex work is morally wrong makes it difficult to correct misconceptions, argue for improved working conditions or work toward decriminalizing the exchange of sex for money. ‘Stigma prevents us from fighting for our rights,’ but ‘if you take away the ‘˜state has the right to legislate morality’ line, then you cannot justify prohibiting sex work,’ McNeill says.

Lately, more sex workers have been coming forward to reframe the issue of prostitution in terms of vocation. Sex work is work, which means that consent is central to the enterprise.

Work is work, right? If you mean, do I prefer this to any other form of employment that I’ve ever tried? The answer is yes. Absolutely. I absolutely prefer it to any other form of employment I’ve ever tried. And it’s way more lucrative and it’s way more flexible. If you mean, would I still do it if I were independently wealthy? The answer is no. No. I would stay at home and write, and read. I’d go travel, do whatever, you know? It’s employment. It’s a job. It is work. One of our slogans, from the sex workers’ rights movement, is ‘sex work is work.’ And that’s a very important thing to keep in mind. It is work. When you try to frame it as something other than work, you get bullshit. ‘Oh, it’s exploitation.’ No, it’s not freaking exploitation, except in the sense that work is exploitative.

Even if we agree that sex work is exploitation, McNeill argues, it doesn’t make sense to criminalize it for that reason; plenty of legal jobs exploit both men and women or include aspects that exploit women exclusively and women’s bodies in particular. So, ‘why do we believe’why do we imagine’that sex work is uniquely exploitative? What’s the thing there?’ she asks.

‘People are obsessed with this idea that there’s this magical mumbo jumbo energy about sex that makes it different from all other human activity,’ McNeill explains, pausing for a second to concede, ‘before there was such a thing as reliable contraception, that may have been true, because it was the only human activity that could create a human life.’ But now we have the technology to prevent pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, so the morality argument becomes more tenuous.

Most of the time, the human activity of sex is not oriented toward creating a human life, even when sex occurs within the context of a traditional heterosexual marriage.

Despite stereotypes, there is a large spectrum of people selling sex, and most women who engage in sex work only do it part time, McNeill explains. But the public debate often misrepresents the perspectives and experiences of sex workers. The majority of contemporary whores are women whose neighbors don’t know what they really do, women who are drawn to sex work because it is so lucrative compared to the other jobs available, women who have kids or loved ones to support but limited saleable skills, McNeill says, adding:

Some hate it, some love it, but the other 90 percent are in between: it’s a job better than other jobs and others say it’s crappy but better than a restaurant. Some days I’m like, ‘I’m being paid for this? This is work?’ Other days, it’s keeping your eye on the clock, biting your lip, ‘What’s this dude doing?’ Like any other job, good days and bad. But you can walk out whenever you want. Freedom to choose.

There has been a lot of media attention focused on women who have been trafficked or coerced into selling sex, but in reality, McNeill says, most women who are sex workers freely choose to do it ‘because we feel it is the best choice for us at the time.’

Even though ‘our society expects men to take advantage of business opportunities,’ it’s different when it comes to women, she explains. ‘Men are usually given the dignity of having done it on purpose.’

If we want to talk about the real problem, McNeill argues, we should talk about a ‘root problem’economic inequality and lack of opportunity.’ Amnesty International and the ACLU agree with her on this point. After much debate, Amnesty solidified its position in May 2016, sharing research documenting how criminal models for consensual sex work’including the much-touted ‘Nordic Model,’ which purports to target only the clients’harm the men and women involved.

When I asked specifically about brothel-based models, McNeill responded, ‘Any model that limits women’s choice is a bad model.’ And I think that sums it up effectively. She went on to discuss the Nevada brothels, which are politically connected to pimps and restrict the women from leaving the premises while employed there. ‘Anywhere that the law requires the women to get a license to operate using their real name promotes non-compliance,’ she added, because ‘then when the laws change you are registered and the cops have a list of women they can rape, coerce, etc., or the newspapers can print a list of the women.’

So the model in Wallace was not the best model possible, since the women were required to register with the Shoshone County Sheriff’s Office and submit to background checks run through the FBI until 1973 (when that practice finally ended), but the businesses in Wallace were women-owned and women-run before 1905 and after 1945. And, according to research I documented in the book, the women were discouraged from being connected to men who lived off their earnings, and they were freer to come and go as they pleased than in Nevada… Now, it seems like many sex worker rights advocates are talking about New Zealand’s model as a positive situation. My own personal opinion is that we should decriminalize sex work, since most women who do it tell us that would be best for everyone involved in the industry.

I don’t really know a very good way to wrap this post up. If you enjoyed reading about McNeill’s perspective, please visit her site and show her some love!

Leave a Reply