First of all, let me just say this: the FBI didn’t close down Wallace’s houses.

That’s the official story around town, despite the fact that the last brothel, the U&I Rooms, stayed open until just a few weeks prior to the raid. People say that the intervention of the federal government was just the final nail in the coffin, that the real reason the century of brothels ended was a result of AIDS and the lousy economy.

In a move that locals would later describe as “overkill,” the FBI sent 150 agents into the Silver Valley and raided almost every bar in Shoshone County (and, accidentally, one or two from Kootenai County as well) from Cataldo to Mullan on this day in 1991.

What most people here say is something like this:

It had nothing to do with the FBI. That’s why they went after the bars, because they’d come to town to put the whorehouses out of business, but they were going out of business anyway. The feds had to recoup their expenses, so they decided to go off in a different direction…. It had nothing to do with the FBI. It had to do with AIDS. (Gnaedinger)

John Posnick, who used to run the Silver Corner, told me he thought the FBI was looking for a drug ring as well. John and Sue Hansen also agreed with this interpretation. Sue added that the way she understood things, an agent tipped off one of the women working at the U&I, “in a moment of weakness,” warning her that they should probably get out of town before the raid went down.

The official story from the FBI remains to be written, although judging from what appeared in the newspapers and the trial, the story is consistent there, too. Federal officials focused on gambling and racketeering rather than prostitution, and did “not so much [target] the machines as the local authorities who had allowed them to flourish” (Egan, “Gambling Raid”). Of course, it’s also not so simple as that…

During the raid, FBI agents took more than a half a million dollars in cash from the bars and ‘seized all the video poker machines’ (Egan, “Gambling Raid”). Of course, locally we know that—as a result of the infamous yet informal “phone tree”—some of those slot machines didn’t actually make it into federal hands because some people were able to rush a few out before the agents could make it to all the bars in the Valley as they moved from west to east. The government kept the money and the rest of what they took unless the bar owners or operators could prove in court that the earnings weren’t the result of illegal activity.

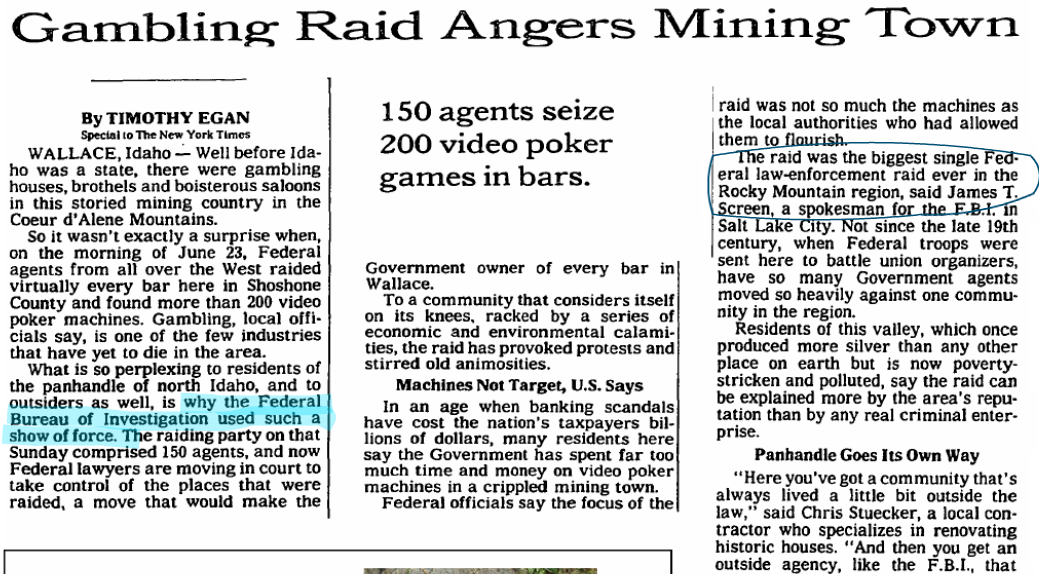

About a month later, in an article titled, ‘Gambling Raid Angers Mining Town’ (Special to the New York Times, 20 August, 1991, A18), Timothy Egan wrote:

it wasn’t exactly a surprise when, on the morning of June 23, Federal agents from all over the West raided virtually every bar here in Shoshone County and found more than 200 video poker machines.’¦ What is so perplexing to residents of the panhandle of north Idaho, and to outsiders as well, is why the Federal Bureau of Investigation used such a show of force….

Not since the late 19th century, when Federal troops were sent here to battle union organizers, have so many Government agents moved so heavily against one community in the region.

The FBI’s interest was the result of disgruntled sheriff’s deputies going to the FBI with concerns about corruption. Sheriff Frank Crnkovich was tried twice for racketeering by the U.S. Justice Department’s well-funded Public Integrity Division.

When I asked Crnkovich’s defense lawyer, Sam Eismann, what his main argument was, he said:

They [the prosecution] had all this fancy gear. So the jury could listen to all the [surveillance] tapes, high-tech stuff. So in my argument I stood up and I said, ‘Well, I’m sorry I don’t have all this high-tech equipment, I can’t afford it, I guess the government can. But what this case is really about is,’ and I wrote on the board that ‘Frank’s a scapegoat.’ And it stayed there during the whole argument, you know, and a couple of jurors after the trial said, ‘That guy was nothing but a scapegoat.’ So if you can put out a little keyword like that in some trials it helps.

Some others were prosecuted along these same lines. Terry Douglas, who began working for Prendergast Amusement in 1978, put his own case this way:

Now, I bought the business March 14, 1989. Three-fourteen-eighty-nine. And then on six-twenty-three-ninety-one, twenty-seven months later, the feds tried to blame me for a hundred years of gambling in Shoshone County.

And even though Crnkovich was not convicted (the first trial ended in a hung jury, while the second trial ended in acquittal), according to his lawyer, the whole episode

broke his spirit. You go through one of these graft and corruption cases, for some reason, it doesn’t matter if you’re found not guilty. It haunts them the rest of their lives. It’s just amazing to me. It just totally changes them. I think you go into a phase where you just want to be undercover because you’ve been through this whole public spectacle, and I bet you think everybody’s staring at you and talking about you, all this stuff, you know, even though you’re not guilty.

Eismann explained that he’d told one of the prosecuting attorneys,

what you really ought to do is get up there and get to know these folks. Get to know why they do what they do. Get to know the history of the community. Get to know why they have to have poker machines in their bars to survive. You know I said, ‘It’s a different world up there, and maybe that will help you understand this, and maybe we can get this case dismissed.’

‘I don’t need to do that,’ the Justice Department’s lawyer responded, ‘I’ve tried these cases [before] and I’ve never lost one.’

Apparently the trial didn’t discuss the women who worked in the brothels in too much depth, but they did talk about the houses as a part of the community’s willingness to accept illegal activity:

We went into what the gals did’the community accepted them up there. They served a purpose, I think, in the old mining days. And they gave band uniforms. They bought the police department a new police car. But it wasn’t the result of any graft, it was just being good to the community, really, for allowing them to be there. The madams did good public relations. I think something like that probably was necessary in the old days, you know, it kept the local gals safe. That’s what some of the old-timers told me.

Regardless of whether or not there was money exchanged, the graft allegation was not confirmed, and the interpretation more in line with the local community understanding is this: yes, the madams and the gambling contributed a lot of money to the community, in both official and unofficial ways, but it didn’t amount to corruption. Many people confirm the existence of a “golden fund” for the city that came from illegal activity, but it was a consensual sort of thing—there was no extortion nor secrecy about it. It was just the way things had always been done, and it was the expectation of the community that it would continue to go on as long as there was money in it.

During their two year surveillance investigation, the FBI apparently bought one of the brothels and was operating it themselves. The rumor is that this is how they caught one of the supposed pay-offs, that there is someone on video accepting an envelope from one of the madams. I don’t know if this is true or not, because I don’t yet have a copy of the trial transcript (if it exists) nor any of the FBI’s evidence or investigative documents.

The trial was well covered by the local papers, and I’ve been able to learn a lot from the people who were personally involved locally, but I’m trying to obtain a copy of the trial transcript and investigative records so I can discuss this whole episode with a bit more accuracy. In closing, I’ll share some of my Freedom of Information Act Request I submitted today:

This is a request under the Freedom of Information Act. The date range of this request is January 1987-December 1995….

On June 23, 1991 there was a large FBI raid on the bars in the Silver Valley in northern Idaho. According to New York Times reporter Timothy Egan, it was the largest ever federal raid in the rocky mountain region. The raid, which had been preceded by a prolonged undercover investigation, involved 150 federal agents and targeted the towns of Wallace, Kellogg, Smelterville, and Mullan, Idaho….

I would like the opportunity to improve the historical accuracy of my book project and enrich its discussion of these events. Please search the FBI’s indices to the Central Records System for the information responsive to this request related to:

All available records and documentation leading up to the June 23, 1991 federal raid and two subsequent trials of Sheriff Crnkovich. Judge Edward Lodge presided over the trials, which took place in Moscow, Idaho. Dan Butler and Nancy Nukem were the prosecuting attorneys for the Department of Justice, and the late Sam Eismann was the defense attorney for Crnkovich.

When I interviewed Eismann in 2010, he told me that the investigation began sometime between 1987 and 1989, after five sheriff’s deputies took records from the Shoshone County Sheriff’s Office and brought them to the FBI’s office in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho or Spokane, Washington. Eismann claimed that the FBI conducted a two-year investigation prior to the raid. I am particularly interested in following up on his assertion that the FBI ‘bought a tavern’ and ‘bought a whorehouse up there…. And they had that all with videotape and were catching pay-offs and stuff…. And there were some people on there that shouldn’t have been, like law enforcement people…. a couple guys rolled over and said there was graft and corruption and payoffs….’

Eismann further claimed that ‘a few days before the trial, they [Butler and Nukem] brought in like 60 or 70 audio tapes and probably 40 or 50 video tapes and I had to review all those at the last minute to see what was on them.’ Eismann recalled listening to these tapes, especially ‘some of the phone calls on the day of the raid. Like one person would call somebody: ‘˜Oh the FBI’s in town.’ And the other person would say, ‘˜Well don’t say anything, this might be taped,’ and then he’d still blab on, you know, it was really something.”

[Name omitted here], who pleaded guilty in an associated case, told me relevant names of informants for the prosecution in connection with the investigation include: [names omitted] (‘confidential informant number 5’)…. If copies of their depositions and/or the Shoshone County Sheriff’s Office records they provided are available, I would like to see these as well.

Thank you very much for any information you can provide regarding these subjects, which I am exploring for scholarly and educational purposes…

Leave a Reply